EBDO on the record: ingesting the project data into the Bodleian Library catalogue

Introduction

It has been our aim from the beginning of the project to make the Shaping Scholarship findings accessible to a wide range of users. From delivering public engagement activities onsite at the Bodleian, sharing our findings with the Bodleian Guides to feed into the guided tours of the Bodleian buildings and disseminating news from the project in these blogs, it is an important component of the project that key details of the processes and findings be as visible as possible. As part of this aim, one of the formal outputs of the project has been to work in conjunction with the Bodleian Rare Books staff and cataloguing team to ingest provenance information accumulated during data capture to the SOLO catalogue. Last year, the Bodleian Library, as Collaborating Partners in the project, recruited a cataloguer to ingest some of our bibliographical data into their catalogue.

Process and methodology

Once the full list of early donors recorded in the Benefactors’ Register to 1620 had been compiled (around 220 in total), and after we had performed brief biographical research on each donor, we were able to select several of these as priority donors for a material survey. This is not the total number of donors for the period, only the donors whose donations were inscribed in the Register. The rationale for selection was designed to pick up on strong or weak associations between the donor and Bodley, and/or Oxford, and/or other donors, as well as other elements such as religious affinity, colonial or international interests. We were also keen to select donors who did not have an ODNB record, so that we could devote research resources to the more obscure members of the donor network. We selected donors who gave books rather than money, as this was more likely to reveal information about the privately owned libraries of the donors.

From October 2022-March 2023 Dr Anna-Lujz Gilbert relocated to Oxford and spent these months surveying the selected items from the Bodleian collections. Anna developed a methodology to capture information according to the project database rationale and which also aligned with the Bodleian’s standards of data description. This was so that there was a common language used between the project and the Bodleian’s online catalogue, SOLO.

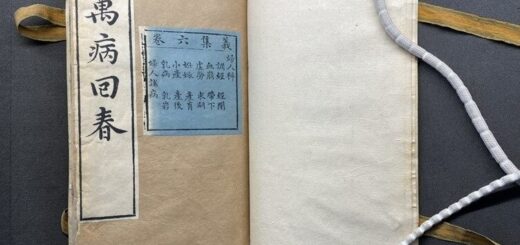

As with most field research, practical issues arose which resulted in amendments to the plan. Reasons such as maintenance issues meant that access to the books in the Bodleian was occasionally restricted. Because of this and other practical and intellectual considerations once the material survey was underway, the list was further revised. For example, some titles were given by multiple donors, and some sammelbande volumes contained multiple titles donated by different people. As a result, descriptions were made for titles donated by non-selected donors. And because of the intermittent access issues to Duke Humfrey’s Reading Room where many of the collections are held, Anna had to prioritise donors whose gifts had shelfmarks from the Medical and Law sections of the library so that work could continue. This meant that the gifts of some donors such as William Gent, a physician and close friend of Bodley, received more attention than others. The image shows Gent’s characteristic purchase code noted in the blank space above the title.

While Anna conducted this research in the field, I began cleaning the material survey data compiled during the pilot project (Building a Library Without Walls: The Early Years of the Bodleian Library) between 2012 and 2017. Although this data had been collected within a project rationale whose research questions were similar to those of Shaping Scholarship, it was important to try and follow the same methodological principles of data collection as those devised for the current project. So, referring to images taken during the pilot study, I edited the material descriptions and added field values in line with the current project database rationale, where possible.1

Drawing conclusions

Part of the process of provenance research was to try to ascertain through material evidence whether the copy now held at the Bodleian was the copy donated by the selected donor. In order to communicate our conclusions methodically once the data had been captured, we constructed a ‘confidence rating’ system which could accommodate varying levels of certainty and uncertainty as to the source of donation. Our conclusions were based on, for example the binding style and decoration, the presence or arrangement of different items within a single binding, the identification of provenance markings and previous owners, and the comparison of previous shelf marks with information in early Bodleian catalogues.

Listed below is the confidence value system, excerpted from our editorial apparatus, and included as part of the editorial documentation shared with the Bodleian towards ingesting this data:

Confidence is given as an integer from 0–5, from least likely to most likely. N.B. each number represents an evenly distributed range within the probability scale, so a confidence value of 0 can be imagined as roughly equivalent to 0–17% confidence, not 0%. Accordingly, that of 5 might be considered roughly equivalent to 83–100%, not 100%.

- 0 was assigned where there was positive evidence that the copy had not been acquired through a given donation. Examples: ownership inscription of John Selden present; evidence of post-1620 private ownership; strong evidence that it was acquired through another donor’s gift, such as a gift inscription.

- 1 was assigned where it was deemed very unlikely, but not altogether impossible, that the copy was acquired through a given donation. Examples: convincing evidence that it was acquired through another donor’s gift (i.e. it had been assigned a 4 in relation to another donation); present at a Seld. shelf mark with no Selden inscription but also no evidence of a pre-Selden shelf mark.

- 2 was assigned where, on balance, it was considered less likely than not that a copy came from the given donation. Examples: at a Seld. shelf mark with no Selden inscription, no evidence of pre-Selden shelf mark, but in a binding that is similar to that of known early seventeenth-century acquisitions; where the binding/shelf mark is characteristic of an early-seventeenth-century acquisition, but where two donors are recorded as having given the same title, and there is either slight reason to suppose the given copy is not the one received through the given donation, or nothing to say either way which of the two donations it came from.

- 3 was assigned where, on balance, it was considered more likely than not that a copy was acquired through the given donation, without there being positive evidence for the same. For a great many copies, this was because the binding and/or previous shelf marks suggest that the book was acquired at around the right time. Taking into account the evidence from the Benefactors’ Register, this was considered adequate evidence to assign as a 3 and conclude that the volume was likely given by the donor. This confidence value was also given for manuscripts identified without certainty in Volume 1 of the Summary Catalogues.

- 4 was assigned when there was good, but not explicit, evidence that a copy was acquired through a specific donation. Examples: where the copy is bound with other titles listed in the same donation; where it bears markings that are characteristic of a particular provenance; where it is in a reasonably distinctive binding or binding style that could be seen on titles associated with a particular donation.

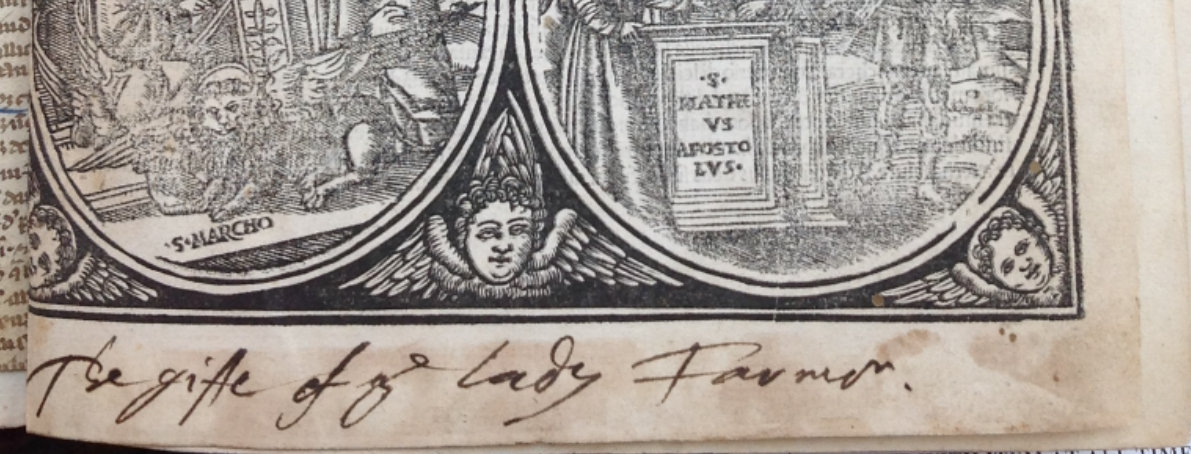

- 5 was assigned where there was explicit evidence that the copy was received through the given donation. Examples: Bodleian-stamped armorial binding of the donor in combination with evidence from the Register; ownership inscription of donor or a family member; gift inscription referring to donor. This confidence value was also given for manuscripts confidently identified in Volume 1 of the Summary Catalogues, unless we had reason to doubt the identification.2

Once the data had been cleaned and combined and confidence values and reasons assigned, we sent the data, our images, our guidelines and documentation to the Bodleian.

The Bodleian cataloguer, Katie Hannawin, developed a workflow to check the data and the conclusions that the Shaping Scholarship team had captured and drawn. Where there were questions over the provenance of a particular item, Katie was able to draw on the advice of in-house experts at the Bodleian and consult the manuscript Bodleian Library Records. In this way, the selected data had a secondary review. Katie was able to assist us in picking up details we had missed or adjusting our confidence rating. Her work was invaluable to the project.

In late September 2024, Katie completed this process of ingestion and was able to confirm that she had added provenance information derived from our project (both Shaping Scholarship and Building a Library Without Walls) for 1,537 print records held by SOLO.

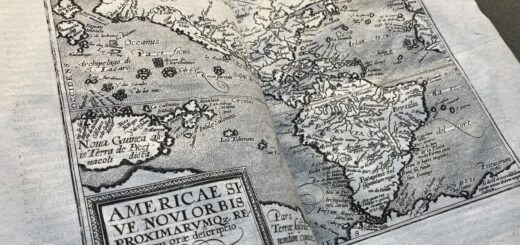

Our provenance research findings can be accessed through searching for ‘Shaping Scholarship’ in the Copy-Specific Notes filter when using an Advanced Search in SOLO. Each catalogue entry updated with information from the project contains a physical description of the book and information relating to whether this is likely to be the book that was listed in the Benefactors’ Register. For example, in 1602 Stephen Rodway donated 37 books, one of which was De Pulsibus libri duo, printed in 1602 in Padua. Anna inspected the item now at 4° R 2(3) Med. and concluded that it was likely that the copy at this shelfmark is the one donated by Rodway, because the binding arrangement matches that implied in the Benefactors’ Register.

The Register reveals that Rodway donated a series of medical works by Eustachio Rudio:

- De naturali atque morbosa cordis constitutione libri tres (Venice: Grazioso Percacino, 1600)

- De tumoribus praeter naturam libri tres (Venice: Giovanni Battista Ciotti, 1600)

- De pulsibus, libri duo (Padua: Lorenzo Pasquato, 1602)

- De ulceribus libri tres (Padua: Lorenzo Pasquato, 1602)

![Registrum Donatorum [Benefactors’ Register vol.1], 1700-1688, Bodleian Library Records b.903, sig. G2r. Image credit: Bodleian Library, Oxford.](https://ebdo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Rodwey-BR.jpg)

These works are bound together in one volume (4° R 2 Med.), so it can be confidently concluded that these are the books given by Rodway.

Checking our data

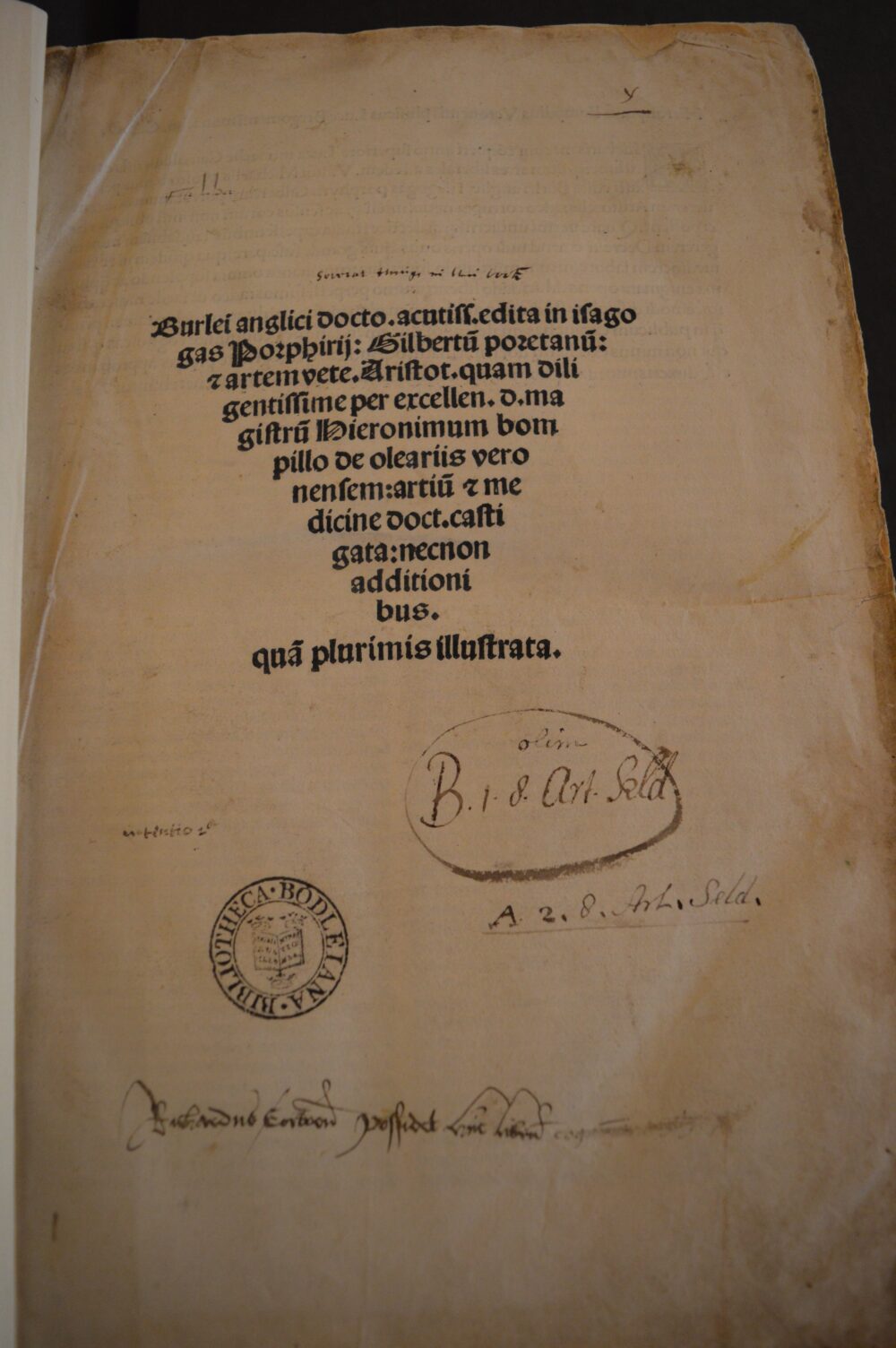

Another example is from the donation of Thomas Kerry, who donated 140 books and one manuscript in 1604. Upon inspection, Kerry’s gift of Walter Burley’s In Isagogas Porphyrii contains minimal evidence that it came from Kerry’s collection, and resembles other books accessioned by the library at this time, i.e. the binding is consonant with early acquisition. We concluded that, despite the presence of a Selden shelf mark (as many non-Selden books were moved to Selden shelf marks over the years) this was likely to be Kerry’s copy and ascribed a confidence value of ‘3’. However, in her review of our findings during the ingestion process, Katie Hannawin was able to cross-refer to the manuscript catalogue of the gift of John Selden’s collection bequeathed to the library which was received in 1659 (Broxbourne 84). As a copy of this work was listed in this catalogue as part of Selden’s gift, and as there was no pre-Selden evidence (i.e. previous Bodleian shelf marks) Katie could conclude that it was more likely that this book came in with Selden’s gift than as part of Kerry’s gift. This follows contemporary Bodleian practice of deaccessioning older gifts from modestly sized donations. We were able to adjust our own data accordingly following her findings.

A book will often contain conclusive evidence that it belonged to a particular owner: inscriptions, monograms, armorial or named bindings, etc. Without this type of firm evidence, it is difficult to make a judgement as to whether this was the actual book donated. But the addition of the physical description and a statement that a book of this title entered the library during this period is nevertheless a useful resource to incorporate into the Bodleian Library catalogue record. As a result of Anna’s survey and the pilot study data, researchers can now access information about nearly 17% of the print donations to the library between 1600-1620. This copy-specific information can reveal rich provenance detail, material features, and enable connections to be made about donors and the deaccessioning of material over the centuries and is extremely useful for book historians, other scholars and library practitioners.

Conclusion

It remains crucial for researchers to communicate these kinds of findings to staff in Special Collections so they can enrich their catalogue records where resources allow. Indeed, while we have been busy collecting data about the books connected to the early donors to the library, work also continues at the Bodleian to survey the materials on the shelves on a format-by-format and faculty-by-faculty basis. Colin Harris, formerly a superintendent of the Special Collections Reading Room at the Bodleian, has spent the last few years since retirement meticulously surveying books from the shelves of the Bodleian, which records are gradually being added to SOLO. During our material survey Colin was kind enough to share his findings from his survey of quarto format books from the Arts faculty so we could cross-reference our data. His is a monumental task conducted over a period of years, and, together with the data collected as part of the Shaping Scholarship project, will assist in enriching bibliographic data for research of this type.

Our thanks to Katie Hannawin, Sarah Wheale and Colin Harris for their invaluable help, assistance and guidance during this phase of the project.

If you are interested in seeing the material survey and other data, you can download the project data here.

Notes

- As part of the data handover, we included statements as to whether the data was compiled during the current project or the pilot project.

- John Selden bequeathed his library of 8,000 books and manuscripts to the Bodleian, which was received in 1659. These were housed in the newly built West End of Duke Humfrey’s Library, and followed the same faculty shelfmark series with the additional suffix of ‘Seld.’ Duplicates were alienated at this point, and some of the existing books in the collection prior to this date were moved within this classification. ‘Summary Catalogues’ refers to Summary Catalogue of Western Manuscripts in the Bodleian Library at Oxford eds. Falconer Madan & H.H.E. Craster, vols. II pt.1 and II pt. 2 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1922).